How to Combat Value-Added Tax Refund

Fraud

Cedric Andrew and Katherine Baer

August 2023

IMF | How to Note 3

Contents Page

I. VAT Refund Fraud 6

A. Introduction 6

B. Background 7

II. VAT Refund Fraud Schemes 10

A. Missing Trader Intra-Community Carousel Fraud 10

B. Other VAT Refund Frauds 187

III. Strategies to Combat VAT Refund Fraud 19

A. United Kingdom 19

B. The Slovak Republic 23

IV. Conclusion 26

BOXES

1. Example of a Single Tax Loss Transaction and Corresponding Contra Transaction 12

2. Deutsche Bank Case Study 15

3. Her Majesty‘s Revenue and Customs Case Study 16

4. Hungarian Customs and Excise Tax Office Case Study 17

5. VAT Reverse Charge Mechanism 21

FIGURES

1. Risk Management Process Model 7

2. A Simple MTIC VAT Carousel Fraud 11

3. Example of a Simple MTIC VAT Acquisition Fraud Scheme 11

4. Example of an MTIC VAT Contra Carousel Scheme 13

TABLES

1. HMRC Estimates of MTIC Fraud (£bn) 23

IMF | How to Note 4

IMF | How to Note 5

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ATO Australian Taxation Office

CASE Center for Social and Economic Research

ECJ European Court of Justice

EU European Union

ETS Emissions Trading System

FATF Financial Action Task Force

GST goods and services tax

GDP gross domestic product

HMCE Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise

HMRC Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

IMF International Monetary Fund

MTIC missing trader intra-community

SARS South African Revenue Service

SRS State Revenue Service (Latvia)

UKBF United Kingdom Border Force

VAT value-added tax

IMF | How to Note 6

Value-Added Tax Refund Fraud

Introduction

The primary aim of any tax administration is to collect the right amount of taxes and duties payable at

the right time and to do it in a way that engenders confidence in the tax system and its administration.

Instances of failure to comply by taxpayers, whether through ignorance, carelessness, recklessness, deliberate

evasion, or fraud, are inescapable. The difference in behaviors is not always clear-cut, particularly regarding

fraud and evasion. Where a taxpayer deliberately defrauds the tax authority by, for example, establishing a

fictitious enterprise, falsifying invoices, or submitting false refund claims, this is—in most countries’ legislation—

fraud and a more serious offense than, for instance, failing to register for tax purposes, underdeclaring sales, or

overdeclaring purchases (in the case of value-added tax or VAT) or deductions (in the case of corporate and

personal income tax), which are generally referred to as evasion. Therefore, tax administrations should have in

place strategies and structures to ensure that noncompliance, in whatever form, is kept to a minimum.

Furthermore, a key role for tax administrations is ensuring that taxpayers understand their obligations under the

tax laws.

The exact obligations placed on a taxpayer will vary from one tax regime to another. However, four broad

categories of obligation exist for almost all taxpayers; the extent to which they are compliant will relate to the

extent to which a taxpayer fulfils these obligations. These broad categories of taxpayer obligation are (1)

registration in the tax system, (2) timely filing or reporting of requisite taxation information, (3) reporting of

complete and accurate information, and (4) payment of taxation liabilities on time. If a taxpayer fails to meet any

of these obligations, then they are noncompliant. How a tax administration determines and manages its

response to noncompliant behavior is through a taxpayer compliance program.

The purpose of a taxpayer compliance program is to identify and react to the most significant risks in

the tax structure by a range of countermeasures that address the underlying cause of the noncompliant

behavior. This requires intelligence-led and evidence-based methodology to identify the highest risks in the

various tax regimes and determining the most appropriate response regarding, for example, allocation of

resources and legislative changes. The development of a compliance program is a cyclical process that permits

a tax administration to organize its compliance risk identification, risk prioritization and compliance strategy

planning that focuses on the most significant risks. In this way, a tax administration with a finite budget can

adjust available resources to the levels of risk across competing tax regimes to ensure that compliance

interventions achieve maximum impact.

Segmenting taxpayers into subcategories of taxpayers with similar characteristics and behaviors

facilitates more precise identification and categorization of compliance risks. This results in a better

understanding of the true compliance risks and helps identify and deliver risk treatments. In a taxation context,

the taxpayer base is typically segmented from the perspective of business, individual, and occasionally type of

tax. Typical segments include small businesses, medium-sized businesses, and large businesses as well as

individuals and the type of tax—direct or indirect.1 Measuring the tax gap (the gap between what tax should in

theory be collected and what is actually collected) contributes to the process of identifying noncompliance in a

taxpayer segment and the behaviors that led to the gap.2 Where the aberrant behavior is due to a taxpayer

1A description of the most common types of VAT-noncompliant behaviors for the large, medium-sized, and small/micro-taxpayers in

Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK can be found in Baer 2013, 12–22.

2See Hutton (2017).

IMF | How to Note 7

acting fraudulently, both compliance and enforcement interventions are necessary to tackle the fraud, all of

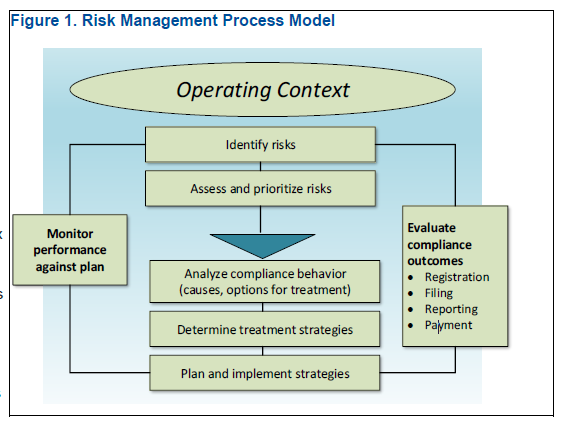

which are informed by a risk management process. For example, see Figure 1.

Tax evasion is an enduring

and intractable problem for

tax administrations around

the world. There is, however,

a wide range of ways in which

a taxpayer can break the law

by not paying the taxes due

and thus contribute to the tax

gap. Importantly, tax

avoidance—which involves a

taxpayer arranging their

financial affairs to minimize tax

liability within the letter of the

law if not the spirit—is not tax

evasion. Tax noncompliance is

generally defined by the

following main behaviors:

▪ Evasion occurs when an

individual or a business fails

to comply with their tax

liability through techniques to circumvent or frustrate tax laws. This can include failure to register for taxation,

where often income from goods and services, usually paid for in cash, is not declared for tax purposes, or

for registered taxpayers, deliberate understatement of taxable income or willful nonpayment of taxes due.

▪ Tax fraud is intentional, criminal activity—which often involves organized criminal groups conducting

coordinated attacks on the tax system. This may include generating fraudulent repayments (an example is

VAT refunds), with varying levels of sophistication and organization.

This note will concentrate on showing the insidious nature and extent of the latter, VAT refund fraud, which is

equivalent to theft of revenue from national treasuries.3

Background

VAT fraud is a global problem that involves the loss of huge sums of money, causing economic harm to

the revenues of national governments. By its very nature, VAT fraud, and in particular VAT refund fraud, is

not bound by fraudsters competing for a finite return on their investment. Instead, it provides a limitless

opportunity to exploit the system to steal money, with criminals cooperating to defraud governments and even

sharing “best practices” to maximize each other’s profits. Global networks designed and tasked to facilitate VAT

fraud have evolved not only to ensure that the criminals can quickly respond to law enforcement

3Much of the focus in this paper is on schemes that reflect particular features of the European Union (EU), characterized by the fact that

exports are zero-rated and there are no border controls. Although some national carousel-fraud schemes are mentioned that may have

elements of the fraud schemes discussed here, given the cross-border nature of Missing Trader Intra Community (MTIC) fraud, much of the

discussion in this paper is relevant to the EU context. Since this paper was first prepared, the UK left the EU (starting with a transition period

from January 31, 2020, to December 31, 2020) and different VAT rules now apply. That said, the analysis in this paper is relevant for both

EU and non-EU countries.

Figure 1. Risk Management Process Model

Operating Context

Identify risks

Assess and prioritize risks

Analyze compliance behavior

(causes, options for treatment)

Determine treatment strategies

Plan and implement strategies

Monitor

performance

against plan

Evaluate

compliance

outcomes

• Registration

• Filing

• Reporting

• Payment

IMF | How to Note 8

countermeasures but also to launder the proceeds of VAT fraud offshore in countries where regulatory controls

are either weak or negotiable.

VAT evasion takes many forms, from the ubiquitous evasion linked to unregistered taxpayers in the

cash economy to complex refund frauds. In its simplest forms, VAT evasion in the former includes failure of a

business to register for VAT and the suppression of cash transactions, thus avoiding VAT altogether. This type

of evasion, as well as the generalized underdeclaration of sales and overdeclaration of purchases, has a

pervasive impact on VAT receipts, particularly for emerging market economies.4 That said, the scale of fraud

experienced and the continuing hemorrhage of revenue from multibillion-dollar VAT refund frauds perpetrated

by organized crime groups pose a significant threat to the management and collection of VAT globally.

Extensive publicity of these large criminal frauds, even if they could be considered as relatively modest

compared to more generalized types of evasion, can erode confidence in the VAT more widely and may weaken

compliance more broadly.

Given the illegal nature of the activity, there are few published estimates of the impact of VAT refund

fraud on tax receipts, and some countries may be understandably reluctant to estimate their losses.

Fortunately, there are now many more estimates of tax gaps, especially for the developed countries—that is,

amounts of tax that are not paid compared to the potential full-compliance payment based on tax laws. These

gaps reflect overall evasion levels. In a few countries (such as the UK), the tax administration has been able to

measure the proportion of the overall gap that is explained by fraudulent activity. Since 2009, the European

Commission has commissioned and published a series of “VAT gap” studies that estimate the difference

between the amount of VAT that would be expected under full compliance and the amount actually collected in

a given year in the member states of the European Union (EU): the “Reckon Report,” published in 2009,5 and

the Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE) studies, published initially in 20136 and updated in 2014

and 2015–2019.7 The published VAT gap for the EU member states in 2013 was almost €170 billion, of which it

was estimated that cross-border (refund) fraud accounted for approximately €50 billion of the total VAT gap—

the balance being attributed to other VAT evasion, legal avoidance, and unpaid VAT liabilities due to

insolvencies. By 2019, The EU-wide VAT gap, which covers all sources of VAT noncompliance, amounted to

€134 billion in nominal terms and 10.3 percent expressed as a share of the VAT total tax liability.

VAT refund fraud and the significant sums involved are not confined to the EU member states. For

example, in 2013 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) started an investigation into a GST8 refund fraud

involving gold where it is estimated that $A700 million was lost to the Australian Treasury over a five-year period

through fraudulent GST refund claims.9 This represented a loss of about 5.5 percent of net GST receipts for the

five-year period. Of concern is the ability of criminal organizations to exploit their closeness to legitimate

business structures and employment of accounting and taxation specialists and lawyers to facilitate and support

their activities, which poses a real and present threat for the VAT system. GST refund fraud continues to be a

clear and present danger to tax receipts: in 2022 the ATO’s sophisticated risk models detected potential

fraudulent GST refund claims in the amount of about $A850 million. False information spread through social

4In 2005, two years before it became a full member of the EU, Bulgaria had VAT fraud estimated at US$435 million to US$870 million, or

25–50 percent, as a percentage of Bulgarian VAT receipts (Pashev 2007).

5See Reckon LLP (September 2009).

6See Barbone (2013).

7See European Commission and others (2021).

8The goods and services tax (GST) in Australia is a value-added tax of 10 percent on most sales of goods and services.

9See Inspector-General of Taxation (2018).

IMF | How to Note 9

media played a role in an unprecedented increase in false GST refund claims (involving nearly 29,000

individuals) that the ATO has forcefully countered through its operation PROTEGO.10

Attacks by organized criminal groups on tax systems to generate substantial profit are not restricted to

VAT and are often linked to other criminality. Globally, criminals who are usually involved in the more

traditional forms of serious organized crime are attracted to frauds against tax systems because they generate

large profits with a relatively low risk of prosecution. Also, criminal acts such as identity fraud and money

laundering are easily adapted to commit tax fraud, particularly VAT refund fraud. For example, it is estimated

that tax crime is one of the top three sources of illegal money laundered through the international banking

system.11 Tax administrations can, therefore, play an important role in detecting and deterring money

laundering—but only if they have the necessary powers to track and trace financial transactions through the

banking system.

10See Australian Taxation Office (July 2022).

11See Financial Action Task Force (2018).

IMF | How to Note 10

VAT Refund Fraud Schemes

Missing Trader EU Intra-Community Carousel Fraud

In 1993, the introduction of the single market brought about important changes in the way that VAT was

charged and accounted for on goods moving between member states of the EU, the result of which was

an alarming increase in VAT refund fraud. Goods supplied between VAT registered traders in various

member states were zero rated on dispatch; but instead of paying VAT on import, the customer in the country of

destination accounted for the VAT due later on their normal domestic VAT return.12 Thus, in most cases, goods

supplied between member states effectively moved VAT free. The intra-community VAT scheme has, however,

resulted in extensive abuse of the system through what has become known as missing trader intra-community

(MTIC) fraud.

MTIC fraud is an organized criminal attack on the VAT system resulting, if successful, in the fraudulent

extraction of revenue in the form of VAT refunds from the treasuries of the member states. The fraudsters

will make their transactions tainted by MTIC fraud appear legitimate (and may implicate honest traders) so that

the transactions can be conducted without alerting the VAT authorities to the fraud. The transaction chains are

also deliberately complex to make it more difficult for VAT audit staff to verify them. In its basic form, MTIC VAT

fraud involves obtaining VAT registration for purchasing goods VAT free from another EU member state, selling

them to another VAT registered trader in the same member state at a VAT-inclusive price, and then going

missing without paying the VAT to the VAT authority. The primary, often only, reason for acquiring a VAT

registration is to steal the VAT.

The two main forms of MTIC fraud are carousel fraud and acquisition fraud. MTIC carousel fraud is carried

out with the aim of submitting a fraudulent VAT refund claim, or sometimes to reduce the amount of VAT that

the trader pays to the VAT administration. Goods are typically imported from another EU member state and then

sold through a chain of contrived transactions before being re-exported, also VAT free. The first trader in the

domestic fraudulent supply chain is the missing trader who acquires the goods zero rated for VAT purposes and

makes a domestic VAT standard-rated sale. The goods will frequently be imported VAT zero rated from another

EU member state. The missing trader will go missing without accounting for the VAT due to the VAT

administration. The trader who eventually exports the goods will fraudulently reclaim their input tax as a refund

from the VAT authority. The intermediary traders in the supply chain who are placed between the missing trader

and the exporter are sometimes referred to as buffers. They typically buy and sell VAT standard-rated goods

making minimal profit and consequently make a minimal payment of VAT to the tax administration. As a rule,

because the supply chains are contrived for the purposes of defrauding the VAT, traders in the chains are aware

they are participating in a fraud, actively working to facilitate its operation. Figure 2 shows an example of a

simple MTIC VAT carousel fraud.

12This is known as the destination principle of accounting for VAT on transactions between member states. The single market, established

on January 1, 1993, abolished border controls for intra-community trade. Starting on that date, VAT-registered suppliers were entitled to

apply a zero-VAT rate on their sales to VAT-registered buyers in other member states. In principle, the VAT should be paid in the member

state where the goods are consumed.

IMF | How to Note 11

With MTIC acquisition fraud, a VAT-registered (missing) trader acquires goods VAT free from another

member state, charging VAT on their onward domestic sale to a buffer company, but then deliberately

fails to account for the VAT due to the VAT administration. The buffer typically sells the goods to a domestic

wholesaler or distributor. Because the supply chains are contrived for the purpose of defrauding the VAT,

traders in the chain are aware they are participating in a fraud, actively working to facilitate its operation. As with

carousel fraud, there may be a complex series of transactions within the supply chain. However, the operation of

acquisition fraud requires a legitimate end customer for the goods, which may eventually be sold for retail

consumption. The fraudsters often undercut genuine traders’ prices when selling their goods because their profit

comes from the VAT they fail to pay to the VAT administration. In an MTIC acquisition fraud, because the

missing trader has no suitable premises, the goods may be delivered directly to the wholesaler or distributor

while the missing trader receives the invoices for the goods. Figure 3 illustrates a simple MTIC VAT acquisition

scheme.

Figure 2. A Simple MTIC VAT Carousel Fraud

IMF | How to Note 12

An MTIC fraud may involve the following players and roles, which are interchangeable regarding both carousel

and acquisition fraud:

▪ Organized criminals: They orchestrate the fraudulent trading activity but rarely operate within the supply

chains themselves. Some are based offshore (for example, in the Middle East and operating across

international borders). Many are also involved in other serious forms of criminality, including drug and tobacco

smuggling, human trafficking, identity fraud, and terrorism.13

▪ Missing or defaulting VAT registered traders: They import goods VAT free from other EU countries, sell

them within the member state where they are located while charging VAT on the sale, but then go missing

without paying any VAT to the VAT authority.

▪ Buffer (or intermediary) traders: They buy and sell the goods within the member state where the fraud

operates, charging and reclaiming VAT on each transaction. The role of the buffer is to disguise the link

between the unpaid VAT at the start of the contrived supply chain and the repayment claim or final customer

at the end of the chain.

▪ Broker traders (applicable to carousel fraud only): They buy goods within the member state where the

fraud operates and then sell them on either to other EU member states or to countries outside the EU. The

broker then submits a VAT refund claim to the VAT authority, which, if paid, will enable the unpaid paper debt

accumulated by the missing trader to be converted into actual proceeds of crime.

▪ End customers (applicable to acquisition fraud only): They are generally legitimate customers who

purchase goods used to carry out the fraud from a buffer trader. Their actions ultimately enable acquisition

fraud to take place.

▪ Other roles: Various other entities operate on the periphery of the supply chains, such as freight forwarders

or warehousing traders, who take the opportunity to make profits based on the large trading volumes

generated by the fraudsters.

To evade detection by the VAT authorities in the EU of the operation of an MTIC carousel fraud, the

fraud has evolved into what is known as contra, or offsetting, MTIC fraud. Put simply, contra fraud involves

13See EU Organized Crime Threat Assessment (Europol 2009).

Figure 3. Example of a Simple MTIC VAT Acquisition Fraud Scheme

WHOLESALER

FRENCH SUPPLIER

MISSING

TRADER

BUFFER

TRADER

INVOICES

MISSING

TRADER

INVOICE

BUFFER

INVOICE

CONSIGNMENT DELIVERED

DIRECT TO WHOLESALER

?

RETAILER

WHOLESALE

INVOICE

IMF | How to Note 13

two contrived supply carousel chains, one of which commences with a missing trader. The second supply chain

is the contra chain. The exporter in the missing trader chain is the acquirer in the contra chain selling goods at

the VAT standard rate on the domestic market, thereby negating or reducing the net tax liability. The purpose of

this scheme is to conceal fraud-related sales, thus concealing the overall fraud. The complex nature of the

contrived transactions involved in MTIC contra fraud is often misunderstood and is worth examining.14

In a contra, or offsetting, MTIC fraud, the broker, who participates in any number of basic fraudulent

MTIC tax loss chains, also acquires (imports) goods from another EU member state. These acquisitions

(imports) are the “contra” transaction chains. The onward supply in the UK of the contra transactions by the first

broker in the chain (broker 1) creates an amount of output tax that reduces or negates the input tax that broker 1

would have claimed with respect to all the tax loss transactions. Accordingly, broker 1 either does not file a VAT

refund claim or claims a much smaller refund than would otherwise be the case. The fact that broker 1 does not

seek a large refund when filing their VAT return permits them to avoid the risk process adopted by the tax

administration that is looking for significant refund claims.

The consignments broker 1 acquired (imported) and sold in the member state are subsequently

exported zero rated for VAT purposes by another broker (broker 2). Broker 1 receives payment for the

contra transaction that includes the amount of money that broker 2 subsequently reclaims as a refund for input

tax from the tax administration. Consequently, until they submit their VAT return, broker 2 is financing all or part

of the VAT element of the fraud. The money received by broker 1 from the contra transactions, including the

VAT portion, is used to fund the VAT in the tax loss chains. If the contra transactions take place in the same

VAT period as the tax loss chains, the net effect is that the VAT portion of the money received by broker 1 from

the contra transactions may pass down the tax loss chains and be dissipated outside the jurisdiction.

Box 1. Example of a Single Tax Loss Transaction and Corresponding Contra Transaction

▪ Transaction A

• Broker 1 purchases goods in the UK, standard rated for VAT purposes, in a transaction

chain that commenced with a missing trader.

• Broker 1 then exports those goods, zero rated for VAT purposes, to another country. Broker

1 subsequently claims an input tax deduction in respect of this export consignment.

▪ Transaction B

• Broker 1 then acquires goods zero rated for VAT purposes from another EU member state

of an equivalent value to those purchased in transaction A.

• Broker 1 then sells those goods at the standard rate for VAT purposes in the UK to a buffer

company, which in turn sells them to broker 2.15

▪ Transaction C

• Broker 2 exports the goods to another country zero rated for VAT purposes, thus reducing

their net tax liability, or generating a VAT refund claim.

• Broker 1 subsequently submits a VAT return for nil net tax, since its input tax claim and

output tax are an equivalent offsetting (that is, the input tax deduction relating to transaction

A minus the output tax liability relating to transaction B equals a net tax liability of zero).

• Broker 2 submits their VAT return for a VAT refund or with a reduced net tax liability.

It is not necessary for the tax loss transaction and the contra transactions to match one for one. It is

simply a case of those orchestrating the fraud moving an amount of money, including the VAT portion, from the

contra transactions to broker 1, who uses the money to fund the VAT portion in the tax loss chains. The money

passes down the tax loss chain and is dissipated. The VAT portion is then claimed back from the tax

administration by broker 2 as input tax.

14 Box 1 provides an example of a single tax loss transaction and corresponding contra transaction.

15In this scheme, the buffer company is not a legitimate trader because all the transactions are contrived to steal money from the tax

administration with the knowledge of all the traders in the chain of transactions.

IMF | How to Note 14

The contra, or offset, transaction chain thus forms part of an overall scheme to defraud the VAT

administration because it forms, in effect, an extension of the original transaction chains commencing

with a missing trader. This form of MTIC fraud was probably introduced in response to tax administrations

delaying VAT refund claims that were subject to an extended verification process. It is also possible that no

goods exist in either the contra or tax loss chain or both, and the fraudsters will, therefore, ensure that

supporting documentation exists in the chain. Consequently, the money flow takes on greater significance,

which in a contra chain is always circular, although payments may be consolidated or split to disguise this fact.

Further, given that the money will normally flow though one or more banks that are outside the jurisdiction, it is

difficult to obtain the financial information necessary to demonstrate the carousel. Nevertheless, the fraud relies

on the presence of circularity in the transaction chains. Figure 4 shows an example of an MTIC VAT contra

carousel scheme.

Traditionally in the EU, MTIC carousel fraud has been limited to the intra-community VAT free supply of

high-value, low-volume goods. Notably, the goods traded in carousel frauds have been cell phones and

computer microchips, but other commodities such as precious metals, copper, razor blades, and even scrap

metal have also been traded through a carousel.16 From analyzing the trade in these commodities, it is apparent

that the volumes traded not only bore no relation to the capacity of the commercial market for which they were

supposedly intended but also distorted trade statistics of national governments. For example, following the

introduction of a VAT reverse charge by the UK in 2007 (discussed below) on computer chips (CPUs—computer

processing units), most which were being acquired (imported) from Ireland, there were questions in the Irish

16Trade in carbon emission credits under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) was a carousel fraud.

Figure 4. Example of an MTIC VAT Contra Carousel Scheme

Acq

Broker

Missing

traders

Buffer

Broker

0%

VAT

0%

VAT

0%

VAT 0%

VAT

0%

VAT

20%

VAT

20%

VAT

20%

VAT

20%

VAT

20%

VAT

0%

VAT

0%

VAT

Tax loss

chain

Conduit Conduit

Conduit

Conduit

Buffer

Buffer

Buffer

Contra

chain

VAT

extracted

VAT

refund

Contra

IMF | How to Note 15

Parliament about the impact this measure had on the country’s GDP because of the fall in exports. Similarly, in

2006, when Dubai was the favored third location through which to carousel goods, a Dubai-based subsidiary of

a mobile phone manufacturer (one of many operating there) whose products were the cell phones of choice for

most UK MTIC carousel fraudsters claimed to have 110 percent of the Middle East cell phone market. Exports

of cell phones to Dubai declined rapidly following the introduction of a VAT reverse charge on cell phones by the

UK in 2007.

Despite concerted efforts by the VAT administrations of the EU member states to combat MTIC carousel

fraud regarding specific goods, the fraud still exists. In response to the efforts of member states to tackle

the problem (for example, introduction in the UK of a VAT reverse charge on cell phones and computer chips),

organized criminal groups have developed innovative variants of the fraud to counter these measures. By

switching to the purchase of cross-border services, which by their very nature are intangible products, the

criminals have made policing these transactions more difficult for VAT administrations. VAT refund frauds

discovered in 2009 involving trade in carbon credit permits demonstrate that intangible products pose a

significant threat to VAT receipts. In its simplest form, the fraud involved a criminal registering to be able to trade

carbon permits in the EU ETS.17 The criminal then starts buying carbon permits in one EU country from another,

free of VAT, and selling them on with the VAT added. But instead of paying the VAT to the relevant tax

authority, they become a missing trader, essentially stealing the amount of VAT collected. In its more

sophisticated form, groups of fraudsters in different countries, in a series of contrived transactions, will send

carbon permits around a circuit among various countries, reclaiming VAT repeatedly before the fraud is

discovered, by which time they have become missing traders and millions in VAT have been lost.18

It was clear that carbon credit fraudsters were fully aware of the potential that trading in intangible

commodities could avoid detection. Such goods or services can be traded without the need to be physically

moved or transported, which represents an obvious opportunity to frustrate the efforts of VAT administrations to

track and trace the transactions.19 At its peak, the extent of the fraud was such that Europol estimated up to 90

percent of all carbon market volume in some EU member states was related to fraudulent activities. Overall,

Europol estimated the EU probably lost at least €5 billion VAT because of carbon trading fraud.20

Such fraud schemes have continued and, indeed, intensified, given the large fluctuations in commodity

prices in recent years that affect the profitability of MTIC fraud schemes. More recently (2022), Europol

estimated that large-scale, criminally organized VAT refund fraud costs EU revenue authorities about €50 billion

annually in tax losses.21

Box 2 shows an example of a prosecuted carbon trading case in Germany.

17The EU ETS was created based on the 1997 Kyoto treaty as a way to curb emissions of climate warming gases and was established as a

cap-and-trade system for transactions of European Union Allowances. These emission rights can be traded like any other commodity on the

market—effectively a financial instrument. The transfer of greenhouse gas emission allowances is a taxable supply of services for VAT

purposes.

18Fraud in carbon credits is not confined to VAT losses and has implications for income tax. The Kyoto Protocol introduced a system of

offsets whereby governments and private companies can earn carbon credits that can be traded in a marketplace. Typically, offsets are

achieved through financial support of projects that reduce the emission of greenhouse gases. The most common type of project is

renewable energy, such as wind farms, biomass energy, or hydroelectric dams. There have already been indications of businesses

“investing” in fictitious carbon offset projects as a means of reducing their tax liability, relying on the inability of tax administrations to verify

the bona fides of the project.

19Considerable possibilities for MTIC fraud involving energy trading (gas and electricity) and mobile phone airtime have been detected.

20See Europol (December 2010).

21See Europol (2022).

IMF | How to Note 16

MTIC fraudsters are well organized and highly resilient, regularly changing their tactics to evade the

interventions of the VAT administrations. It is noteworthy that the overall pattern of MTIC trading does not

appear to be governed by normal commercial factors. Instead, it appears to reflect changes in the fraudsters’

confidence levels in response to major court rulings, or changes in a VAT administration’s strategy for tackling

MTIC carousel fraud and operational activity, for example:

▪ Trading activity in the UK associated with fraud fell significantly in 2003 and 200422 after the introduction of

joint and several liability.23

▪ Fraud-related trading activity in the UK began increasing in early24 2005 after the Advocate General’s ruling in

the European Court of Justice (ECJ) case of Bond House,25 which cast doubt on a legal argument deployed

in the UK to deny suspect VAT refund claims from those operating in MTIC carousels.

▪ Fraud levels in the UK remained low in 2007

26 when the ECJ ruled on what became known as the Kittel

case,

27

which established that when a trader knew or should have known that they were participating in a

transaction connected with VAT fraud, then the trader’s entitlement to deduct VAT can be refused by the VAT

administration. See Box 3 for an HMRC case study.

22See European Union Committee (2007).

23In the UK, the 2003 Finance Act introduced the concept of “joint and several liability” into the VAT Act 1994, the purpose of which was to

hold businesses within the supply chain jointly and severally liable for the VAT that had not been remitted by other businesses in the series

of supply chain transactions. The legislation provided that a business could be made jointly and severally liable for stolen VAT if it had

reasonable grounds to suspect that VAT would go unpaid anywhere in its transaction chains.

24See European Union Committee (2007).

25See European Court of Justice (2006a). Bond House and others joined cases ECJ C-354/03, C-355/03, and C-484-/03.

26See Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (2016).

27See European Court of Justice (2006b, 2006c).

Box 2. Deutsche Bank Case Study

Case Study 1: In June 2016, a German court found seven former Deutsche Bank AG managers guilty of

participating in a VAT refund fraud involving carbon emissions trading. According to the judge, the bankers

participated in a “criminal business model” that resulted in €145 million of fraudulent VAT refund claims.

Per the court, the managers either turned a blind eye to the “clear indications” that the carbon transactions

were set up to defraud the tax authorities or failed to do enough to stop them. In 2011, six men who ran

sham companies that traded emission certificates with Deutsche Bank were found guilty of defrauding

€260 million in false VAT refund claims. The case was part of a major crackdown on carbon emissions–

related VAT refund fraud since the EU began its cap-and-trade system in 2005 and involved police raiding

Deutsche Bank twice over three years. In addition to the imposition of prison sentences, Deutsche Bank,

Germany’s largest bank, paid VAT arrears and penalties totaling €220 million.

IMF | How to Note 17

MTIC fraudsters have exploited a fragmented EU VAT system and lack of fiscal cooperation between the

member states. Because of their fiscal autonomy, EU member states are responsible for developing their

strategies and countermeasures to combat VAT refund fraud, but the globalization of criminal tax fraud has

meant that tax administrations can no longer operate at a national level if they are to provide an effective

response. The EU Commission has frequently stated that one of the “weakest links” in the EU VAT system is

the lack of cooperation between the member states, emphasizing that cooperation between the VAT authorities

must be improved to minimize lucrative cross-border VAT frauds prevalent throughout the EU. The lack of timely

exchange of information between member states has been a fault line running through the EU VAT system for

many years.

In 2009, the EU Commission proposed several changes to improve cooperation between the member

states to combat VAT fraud.28 These included the creation of a decentralized network of VAT fraud experts

from national tax administrations. The aim of the network, called EUROFISC, was to improve cooperation to

detect fraudsters at an early stage and provide an opportunity for mounting joint investigations. Other changes

proposed included direct access to national databases for other member states to enable prompt detection of

cross-border fraud and, importantly, the setting up of common minimum standards for registration and

deregistration of taxable persons in member states. While these were all positive measures and key elements of

the EU Commission’s published strategy for tackling intra-community VAT fraud, the key would be the

development of the member states’ strategic approach to compliance risk management and their ability to

accomplish the plan.

The EU Commission adopted a new VAT action plan in April 2016,29 which set out urgent actions to

tackle the VAT gap and long-term strategic solutions to overcome VAT fraud, particularly cross-border

refund fraud.30 Although the overall and long-term aim of the action plan is for a simpler and fraud-proof VAT

28See European Commission (2008).

29For a discussion of the short-term and medium-term tax policy and tax administration actions proposed, see European Commission

(2016).

30Some measures that the action plan considers that fall more into the scope of VAT design, or policy, include the application, on a

temporary basis, of a reverse charge mechanism (explained below); establishing a robust, single European VAT area that would treat crossborder

transactions in the same way as domestic transactions; thus, business-to-business supplies of goods in the EU would be taxed in the

same way as domestic supplies; and options for greater flexibility regarding the setting of VAT rates, including reduced rates, by member

states. Reverse charge mechanism means that under a generalized reverse charge system, VAT is suspended along the whole economic

chain and is charged only to consumers. This means that total VAT collection is shifted to the retail stage. Such a system does not have the

self-policing nature of the current VAT system (that is, under the principle of fractionated payment), which ensures that a small number of

fairly large, reliable taxable entities in the economic chain account for most of VAT. A final comment: The discussion of VAT policy options to

address the issue of the dramatic impact on VAT revenues of the zero rating of exports within the EU falls outside the scope of this paper.

Box 3. Her Majesty‘s Revenue and Customs Case Study

Case Study 2: In 2006, when MTIC losses were at their peak in the UK, Her Majesty’s Revenue and

Customs (HMRC) took the decision to deny a VAT refund claim of £6.8 million from a business whose trading

activities were typical of those connected with MTIC fraud. Registered for VAT to trade in one commodity, the

company quickly changed its trading activities to dealing in central processing units (CPUs) supplying “gray

market” customers in other member states and the US. From a standing start and with no previous

experience of the CPU business, the two-man company had a turnover of £108 million in a 44-week period.

Following an extended verification of the company’s transactions, HMRC found such hallmarks of MTIC fraud

as fixed profit margins on transactions, third-party payments, and recycling of CPUs and that every

transaction started with a missing trader who had failed, dishonestly, to account for the VAT. HMRC believed

the directors of the business had the means of knowing that the previous transactions were fraudulent and,

as a consequence, lost its right to deduct the input tax under the European Court of Justice Kittel ruling.

IMF | How to Note 18

system in the EU, a few immediate measures have been recommended to address disparities in the way that

member states tackle intra-community VAT fraud. Of the 20 measures in the action plan to tackle the VAT gap,

there are specific recommendations for improving the way in which information on VAT fraud is exchanged and

used and, in recognition of the role of organized crime in carousel fraud, closer cooperation between tax

administrations and other law enforcement authorities.

Other VAT Refund Frauds

False VAT refund claims are a form of VAT fraud in which a business submits VAT returns claiming a

net repayment of VAT based on, for example, zero-rated exports supported by false export documents

or certificates of shipment. The goods themselves remain in the country and are sold on the domestic market

at a VAT-inclusive price, usually for cash and unrecorded in both the vendor’s and the purchaser’s business

records. They may also be sold under cover of false sales invoices to dupe prospective buyers about the

authenticity of the transaction and to add further VAT to the profit.

Bogus companies register for VAT for the sole purpose of generating fictitious invoices that are used by

other registered businesses to either reduce their VAT liabilities or inflate their VAT refunds. VAT

repayment frauds can be single-cell frauds (that is, where one individual or business is involved) or

multiple cells (where a systematic attack on the VAT system is undertaken by one or more individuals

using several businesses). The bogus companies trade for a short period, never submit a VAT return, and

disappear before the VAT administration can act against them. An example of a VAT fraud case uncovered by

the Hungarian Customs and Excise Tax Office is in Box 4.

The use of bogus companies to perpetrate VAT refund fraud can have a significant impact on revenue

receipts in economies experiencing an economic downturn. For example, in Latvia in 2010, when the

country was still recovering from an economic downturn, the State Revenue Service (SRS) calculated that in the

first six months of the year 9.5 percent (LVL 23.6 million) of VAT refunds were claimed by 36 percent of refund

claimants using fictitious transactions. In the same period, 3.4 percent (LVL 249.9 million) of VAT input tax

deductions were based on known fictitious transactions.31 In the previous three years, the SRS detected and

deregistered more than 5,000 bogus businesses, which demonstrates the significant risk to revenue posed by

bogus companies registering for VAT for the sole purpose of creating fictitious sales invoices.

The zero rating of exports provides an obvious temptation for VAT traders with criminal inclinations,

particularly where there is a dysfunctional relationship between the VAT administrations and customs.32

31International Monetary Fund Fiscal Affairs Department (November 2010).

32This is the case generally in countries with a VAT, not only EU member states.

Box 4. Hungarian Customs and Excise Tax Office Case Study

Case Study 3: In October 2009, the Hungarian Customs and Excise Tax office reported that they had

uncovered an international VAT fraud that had been operated by an organized criminal group. The fraud,

which is believed to have cost millions of dollars in lost revenue, operated in several countries, including

Germany, Slovakia, Austria, and some countries in Asia. As part of the fraud, the criminal organization

imported a range of computer parts from various countries in Europe and Asia and then sold them in

Hungary without paying VAT. A total of 38 companies were involved in the fraud and evaded paying VAT by

claiming they had exported the goods to Slovakia, Slovenia, and Romania using forged documents. In

addition, the criminal organization established a bogus invoice factory that provided approximately 80

companies with fraudulent invoices. It is estimated that the fake invoice factory cost the Hungarian

government about US$10 million in lost revenue.

IMF | How to Note 19

Trade facilitation has meant that customs conducts very few export examinations and, where such freight

examinations are conducted, the VAT refund fraudster will rely on fictitious sales and export documents and the

physical presence of a shipping container to circumvent inspection. For example, shipping containers

supposedly containing VAT zero-rated exports of industrial machine tools have been found to contain scrap

metal of the identical weight to the machine tools. Similarly, containers of high-value clothing have been found

on examination at export to contain used clothing for recycling that might, on cursory examination, have passed

inspection. In both cases the exports were linked to VAT refund frauds where the actual goods either did not

exist or were sold "off record” on the domestic market.

Because of the significant sums of money involved, combating fraudulent VAT refund claims is a

priority for most VAT administrations. The following examples of VAT refund frauds discovered by the South

African Revenue Service (SARS) demonstrate the significant damage to revenue receipts caused by the frauds.

▪ In 2015, the SARS alleged that between 2005 and 2008, a businessman claimed more than R250 million

(US$18.75 million) in fictitious VAT refunds.33 The fraud was achieved through a combination of false claims

of exporting fish with a value more than R3 billion, fictitious purchases of fishing vessels, and other activities

involving false purchase invoices.

▪ In 2016, the SARS made several arrests in connection with a multimillion South African rand VAT refund

fraud. The SARS alleged that the VAT suspects did not operate a business or purchase goods from suppliers,

but the VAT refunds they claimed were based on fictitious purchases with a value of R823 million (US$61.73

million).

Not all VAT refund fraud is dependent on false invoices or fictitious exports. Some refund frauds exploit a

loophole in the VAT regulations that unwittingly permits revenue leakage until the lacuna in the regulation is

recognized and closed. As mentioned in the Background section of this paper, in 2013 the Australian Taxation

Office (ATO) began an investigation into goods and services tax (GST) refund fraud involving gold. The fraud

concerned the purchase of gold bullion from a bullion house that, for GST purposes, was treated as currency;

therefore, the transaction was not subject to GST. The fraudster who had purchased the gold bullion would then

break it down into scrap gold, which technically converted it into unrefined gold. The fraudster would then sell

the unrefined gold to a refiner, adding GST at 10 percent to the transaction. The refiner would subsequently

reclaim the GST as input tax, but the fraudster would disappear without paying the GST to the ATO. The fraud,

which was stopped in 2016, is estimated to have cost $A700 million in lost revenue over a period of 5 years.34

Another fraud pattern that the ATO detected around 2008–2009 was the submission by traders of large

numbers of small refund claims—a pattern that was quickly detected and acted on. The more recent (2022)

GST refund fraud scheme has involved a very large number of individuals setting up fictitious businesses and

claiming GST refunds, individuals claiming GST based on fictitious invoices, and individual taxpayers providing

their login credentials to third parties who then file false GST refund claims. As mentioned earlier, this massive

GST fraud scheme was facilitated by false information spread via social media.

33To put this in context, this is equivalent to 0.2 percent of total VAT revenue in 2008. Although a significant sum in absolute terms, it is a

small proportion of overall VAT revenue collected.

34Evidence of ATO officials before a hearing of the Australian Senate, March 2017.

IMF | How to Note 20

Strategies to Combat VAT Refund Fraud

Because of their fiscal autonomy, EU member states are responsible for developing their strategies and

countermeasures to combat VAT fraud, but the globalization of criminal VAT refund fraud has meant

that VAT administrations can no longer operate at a national level if they are to provide an effective

response.35 To tackle criminal VAT refund fraud, particularly carousel fraud, there needs to be good

cooperation not only internationally between VAT administrations but also nationally among tax authorities,

criminal investigators, prosecutors, and the judiciary. This is because carousel fraud is “not just a tax law issue,

it is also, and perhaps primarily, a criminal law issue.”36 It is also, as discussed earlier, a tax policy issue, as

reflected by the policy options that the European Commission proposed in its 2016 VAT Action Plan. Some

countries, however, are inclined even at the national level to limit cooperation between tax administrations and

law enforcement agencies—often due to the lack of legal gateways to exchange information. To reduce the

revenue loss from criminal tax fraud, tax administrations not only must improve their overall compliance

procedures but also can initiate criminal investigations and prosecutions of the perpetrators of the fraud.

Consequently, when criminal organizations are discovered persistently and systematically attacking the VAT

base, and disruption and regulatory action are insufficient to stem their activities, enforcement by criminal

prosecution should be a key component of any strategy to combat VAT refund fraud.

Effective enforcement action is underpinned by an effective risk management system. This is important

not only for tackling VAT refund fraud but also for identifying and dealing with VAT fraud in the informal

economy. Although most tax administrations have risk management structures in place, their effectiveness and

ability to direct fraud-related audit activity and fraud interventions vary greatly. There is little point in a tax

administration identifying a risk if it then fails to properly deal with the problem because of inadequate

deployment of resources to achieve behavioral change rather than a temporary fix. An effective antifraud

strategy must, therefore, be designed not only to identify areas of greatest risk but also to direct the deployment

of resources to counter those risks. Numbers, in human resources, are therefore essential to the success of the

strategy.

Strategies to combat VAT refund fraud need to be dynamic and capable of adapting to new

circumstances to keep ahead of the fraudsters, and they also must not be overly burdensome for honest

traders. The key objectives of any strategy should be to minimize the impact of VAT refund fraud on VAT

receipts, maximize the recovery of stolen revenue, deter the criminals from attempting to commit other frauds,

and impose civil or criminal sanctions against those orchestrating and participating in the fraud. At the same

time, revenue protection and enforcement measures should not be overly costly for honest traders and should

not dampen competitiveness. A VAT refund fraud strategy should be proportionate and targeted, risk based and

underpinned by intelligence data, and designed to ensure that interventions are focused on the organized

criminal groups and operators of suspect or fictitious supply chains. Such an approach also recognizes the

value of minimizing the impact of fraud-combatting measures on legitimate businesses. The following are

examples of VAT refund fraud strategies that various countries have deployed.

United Kingdom

A strategy to tackle MTIC VAT has been in place in the UK since September 2000. The strategy was

designed by Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise (HMCE) and now by HMRC to target areas of highest risk by

identifying tax loss and potential tax loss and, by using a range of interventions—both civil and criminal—to

35Several attempts were made, unsuccessfully, to obtain examples from developing and emerging market countries’ experience with

combatting VAT refund fraud.

36Van Brederode (2008), pp. 34–35.

IMF | How to Note 21

disrupt the fraud at the earliest opportunity. The strategy involved the coordination of a range of activities across

HMCE and working closely with external stakeholders such as HM Treasury, UK Border Force, (UKBF) other

law enforcement agencies and other EU member states. A key element of the initial strategy was enhanced

VAT registration checks to detect and prevent bogus registration applications and thereby exclude potentially

fraudulent businesses from the VAT regime.

Preventing VAT refund fraud through the application of enhanced VAT registration checks that deny

potential fraudsters the opportunity to enter the VAT system is more cost effective than detecting a

refund fraud after registration as the result of audit action. Enhanced registration checks are based on the

application of risk parameters that establish the legitimacy and commerciality of the business or individual

seeking VAT registration and prevent them from entering the VAT system solely for committing VAT refund

fraud. The parameters can also be applied during an early postregistration visit in circumstances of insufficient

grounds to deny VAT registration but ongoing concerns about the legitimacy of the business. Preventing

businesses from registering for VAT may seem counterintuitive when tax administrations are seeking to expand

their tax base. However, an analysis of the VAT registration applications made by bogus companies who

registered to subsequently participate in VAT refund fraud reveals that their applications to register for VAT

would have failed enhanced registration checks, thus preventing them from being registered for VAT.

As MTIC fraudsters quickly overcame any temporary setback resulting from HMCE/HMRC enforcement

activity by developing new forms of fraud, the UK strategy evolved to counter the new threats. To

establish the circularity and contrived nature of the transaction chains underpinning fraudulent refund claims, the

UK relied heavily on EU administrative cooperation mechanisms to obtain (and exchange) information about

suspected MTIC fraud, such as Council Regulation (EC) No 1798/2003 and, more recently, Council Regulation

(EC) No 904/2010.37 It became apparent to certain organized crime groups that by changing the export

destination of the goods being used in contrived transactions from an EU member state to a third-country

destination, they could avoid these being subjected to a verification process to establish the legitimacy of

the trade. This was countered by the UK relying on existing mutual assistance and cooperation

arrangements between customs agencies (for example, Naples II Convention on mutual assistance)38 to

obtain information about the movement of suspect goods. This was particularly effective in exports of cell

phones from the UK to Dubai and Switzerland.

MTIC carousel fraud peaked in the UK during 2005–06. Losses during that period were estimated to be £4.5

billion to £5.5 billion (see Table 1). By 2009 the UK strategy was fully formed, incorporating a wide range of

antifraud measures. The key interventions of the strategy included and focused on the following:

▪ Centrally coordinated intelligence gathering and risk and intelligence analysis

▪ Enhanced identification of possible fraudsters at the VAT registration stage, refusing or delaying applications

until satisfied that the application was genuine

▪ Undertaking preregistration visits in cases where it was suspected that the VAT application was associated

with MTIC fraud

▪ Upon receipt of a repayment claim, centralized and automated credibility checks based on setting correct

credibility parameters to match national risk

▪ When tax was at risk, wide use of security provisions to request a security as a prerequisite to a trader

supplying goods

37Both regulations set out administrative cooperation arrangements between the EU member states for combating fraud in the field of valueadded

tax (European Commission 2003, 2010).

38The Naples II Convention covers mutual assistance and cooperation between customs administrations (European Union 1997).

IMF | How to Note 22

▪ Extended verifications of VAT returns from known or suspected MTIC carousel fraud brokers and denying

input where it could be shown that the broker had knowledge or means of knowledge that they were involved

in the fraud (that is, the Kittel ruling)

▪ The introduction of legislation that provided that a business could be made jointly and severally liable for

stolen VAT if it could be demonstrated that it had reasonable grounds to suspect that VAT would go unpaid

anywhere in its transaction chain

▪ The introduction of a reverse charge system for the sale of cell phones and computer chips39 (see Box 5)

▪ Conducting criminal investigations and prosecutions of the “guiding minds” behind the fraud as well as

selective prosecutions of other participants in the fraud

▪ Monitoring of cross-border movements and scanning or stamping selected consignments to identify

recirculation in partnership with UKBF

39 A domestic reverse charge for cell phones and computer chips was implemented in the UK on June 1, 2007, to remove the opportunity

for fraudsters to use these goods to perpetrate MTIC carousel fraud. As an exception to the normal accounting rules for VAT, the UK

secured agreement to derogate from EU law to apply this antifraud measure, which originally ran until April 30, 2009. The derogation was

then renewed in 2009 and again in 2011. A zero rate for emissions allowances was introduced on July 31, 2009, as an interim measure to

halt rapidly escalating MTIC fraud in this area, pending agreement on a common EU-wide countermeasure. A directive providing an option

for all member states to introduce a reverse charge was adopted in March 2010, and the UK’s reverse charge for emission allowances was

implemented on November 1, 2010.The EU legal base for the reverse charge for mobile telephones and chips has now been superseded by

the reverse charge mechanism. The directive also has the effect of extending the period of validity of the reverse charge for carbon credi ts

from June 30, 2015, to the end of 2018. The reverse charge mechanism allows EU member states the option to introduce a reverse charge

without a derogation for other goods and services subject to MTIC fraud; these are gas, electricity, games consoles, tablet computers,

laptops, industrial crops, and raw and semifinished metals.

Box 5. VAT Reverse Charge Mechanism

A VAT reverse charge transfers the obligation to pay output tax from the supplier to the customer, but the

customer retains the right to deduct VAT on purchases. This means that at each stage a business is in a

net nil tax situation, and the opportunity to commit MTIC fraud is removed. A reverse charge applies only

to business-to-business transactions and the normal accounting rules apply on sales to final consumers.

Therefore, the following actions are no longer possible:

• The missing trader cannot disappear with the VAT paid to them by their customer but owed to the tax

authority.

• Traders cannot divert the VAT due to be paid by their suppliers through third-party payments.

• The exporter cannot claim a VAT repayment from the tax authority.

In June 2007, the UK introduced a domestic reverse charge in respect of wholesale trade in computer

chips and mobile phones and, in July 2009, carbon credits, which were the commodities most commonly

used in UK carousel fraud supply chains. The effect of these legislative changes was to stop MTIC

carousel fraud in these commodities, resulting in a reduction in revenue losses.

Having said all that, in a sense adopting the domestic reverse charge mechanisms is still an ad hoc and

piecemeal approach, with government playing catch-up with fraudsters. This mechanism also undermines

the fractal character of the VAT and means there is no longer a “transactions trail” for the tax

administration to follow as a basis for VAT audit and compliance control activities.

The distortions introduced in the operations of a “normal” VAT by a reverse charge mechanism might

argue for more fundamental policy response. While recognizing this, a more detailed discussion of these

policy options is beyond the scope of this paper.

IMF | How to Note 23

The strategy was underpinned by centrally coordinated intelligence collection garnered from disruption

and enforcement activity. The intelligence was used to refine risk assessment criteria applied at the

registration stage and to identify shifts of fraudulent activity to other sectors or commodities (for example, the

evolution from goods to intangible products such as carbon credits). Additionally, the strategy aimed to

maximize the use of international crime and tax fraud fora in the EU and internationally to raise awareness of

MTIC fraud and to support proposals for improving information exchange and cooperation between member

states and third countries. For example, the UK used the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to raise

awareness of how the proceeds of MTIC fraud were being laundered through the international banking system.

The FATF recommended that the financial intelligence units of its member countries use the mechanism of

suspect transaction reports to report suspicious money flows that may be related to MTIC fraud.40

VAT refund claims have always been subject to centralized and automated credibility checks on receipt

by HMCE/HMRC as a key component of the MTIC strategy. The process involved subjecting claims to a

range of separate checks based on individual parameters that were variable, enabling refund claims within

predetermined risk bands to be targeted. The current procedure that HMRC uses is an automated risk

assessment system called TRUCE (Transaction Risking Upstream in the Connect Environment41) that profiles

VAT refund claims in real time to identify those where there is an increased risk of fraud.42

The MTIC strategy had a dramatic impact on the levels of MTIC activity and subsequent losses in the

UK. The various elements of the MTIC strategy, particularly dislocation of supply chains, criminal prosecutions,

recovery of assets both civilly and criminally in the UK and internationally (such as Dutch Antilles and Dubai),

and the reverse charge on selected commodities, were highly effective in suppressing carousel fraud. Similar

tactics were subsequently deployed to tackle acquisition fraud, to which many fraudsters gravitated after their

attempts to commit MTIC carousel fraud were stopped. Losses from MTIC fraud peaked in 2005 at £4.5 billion

to £5.5 billion (see Table 1) when it was estimated that the UK accounted for 25.4 percent of all EU losses from

carousel fraud.43 The downward trend in MTIC fraud losses was sustained in subsequent years, and the MTIC

fraud estimate for 2014/15 was between £0.5 billion and £1 billion, which is within the same range as for

2013/14 (see Table 1).

The MTIC fraud estimate fell to less than £0.5 billion in 2016/17, from between £0.5 billion and £1 billion

in 2015/16, and from its peak of £2.5 to £3.5 billion in 2005/06. Given the downward trend for this form of

fraud, the UK HMRC’s Tax Gap study no longer disaggregated this type of fraud separately from the overall

VAT gap in 2017/18.44

40See Financial Action Task Force (February 23, 2007).

41Connect is an analytical and sorting computer system that HMRC introduced in 2009 and is used to carry out the preliminary work before

commencing an audit or investigation. The system links taxpayers to more than one billion pieces of information held in the system, which is

fed from 28 data sources such as Companies House, the Land Registry, Benefits Agency, and onshore and offshore banks. Connect

produces data linking a taxpayer to property addresses, companies, partnerships, and trusts and is a platform that works across direct and

indirect taxes such as VAT.

42The IMF is providing advice to many emerging market and developing countries on introducing risk-based systems to manage VAT

refunds, although countries’ capacity to implement such systems differs significantly based on the degree of maturity of their tax

administration. At the same time, the increasing rate of digitalization of tax procedures, including, for example, the widespread adoption of

electronic VAT invoicing systems in many emerging market and developing countries, suggests that large-scale automatic verification

systems similar to those that more advanced tax administrations use could soon be a reality in many (though not all) tax administrations.

43See Reckon LLP (September 2009).

44See Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (2019).

IMF | How to Note 24

Table 1. HMRC Estimates of MTIC Fraud (£bn.)

2005/

06

2006/

07

2007/

08

2008/

09

2009/

10

2010/

11

2011/

12

2012/

13

2013/

14

Attempted

fraud

Upper bound 5.5 4.5 2.5 2.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Lower bound 4.5 3.5 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5

Impact on VAT

receipts

Upper bound 4.0 3.0 2.5 2.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Lower bound 3.0 2.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5

Source: Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs 2009 (revised 2010); 2015; 2016.

Note: HMRC = Her Majesty’s Registry and Customs; MTIC = missing trader intra-community; VAT = value-added tax.

The Slovak Republic

VAT losses in the Slovak Republic grew steadily after Slovakia’s accession to the EU in 2004, with the

VAT gap peaking at just over 40 percent in 2012.45 Risk indicators and revenue authority intelligence at this

time pointed toward the severe losses resulting from organized large-scale fraud, particularly MTIC fraud.

Subsequent analysis conducted in 2013 showed unusually high input tax credit claimed against VAT supposedly

paid on imports that were higher than the amounts of import VAT declared—a clear indication of potential VAT

refund fraud. Also, a VAT gap study published by the Slovak Institute for Financial Policy in 2012 reported that

the VAT gap in 2010 amounted to about a third of the tax base (about €2.1 billion or 3.5 percent of GDP). The

inescapable conclusion was that the scale of the VAT gap was the result of systematic MTIC-type VAT frauds

perpetrated by criminal gangs or individuals.

High-profile investigations into VAT refund frauds confirmed the significant level of VAT evasion in the

Slovak Republic. In one case, from 2007 to 2010 a Slovak businessman is alleged to have made fraudulent

VAT refund claims of more than €32.7 million, mostly based on fictitious transactions between companies that

had no employees and were all controlled by the alleged fraudster. Also, in what is believed to have been

Slovakia’s largest VAT refund fraud, nearly €45 million was (anecdotally) stolen by 30 companies, controlled by

an organized crime group, which were established for the sole purpose of submitting false VAT refund claims.46

In 2012, the Financial Administration of the Slovak Republic announced an action plan to combat tax

evasion and VAT fraud, which was implemented in 2013 and 2014.47 The action plan was motivated by the

scale and growth in the VAT gap and compliance risks in other taxes. The plan consisted of 50 measures

intended to counter tax evasion and fraud, particularly in relation to VAT. The measures introduced included

both legislative changes and interventions by the tax administration. Some of the key measures in the action

plan included the following:

▪ Requirement for a financial guarantee for high-risk traders when registering for VAT

▪ Joint and several liability provisions

▪ Extension of the domestic reverse charge mechanism

▪ An obligation to provide evidence of intra-community deliveries

45Figures provided by country authorities. See also European Commission (2017).

46Various reports in the Slovak Spectator newspaper.

47See Decree No. 380/2015, which approved amendments to Action Plan to Combat Tax Fraud in 2012–16.

IMF | How to Note 25

▪ Requirement for a tax guarantee in respect of goods imported from third countries

The action plan also required the establishment of specialized tripartite teams comprising tax specialists,

investigators and prosecutors and known as Project Cobra to deal with serious tax crimes. To support the work

of these teams, the plan also required changes to the criminal law to deal with tax fraud:

▪ The introduction into criminal law of a new offense of tax fraud

▪ More stringent penalties for substantial tax crimes

▪ Introduction of courts specializing in tax crimes

▪ A change to the organization of the police to set up specialized task forces to combat serious economic

crimes

Following the implementation of the action plan, the Financial Administration reported a significant

improvement to VAT collections, with results improving from 2013 onward. According to figures from the

Slovak Financial Policy Institute, during the period 2012 to 2017, audit and investigation activity attributable to

Project Cobra resulted in VAT adjustments totaling €807 million, of which about €152 million was accounted for

by VAT refunds. Also, the Financial Administration found that, following the introduction of the requirement that

VAT traders submit recapitulative statements with their VAT returns,48 there was an overall improvement in the

accuracy of returns data from around 80 percent to 96 percent. The recapitulative statements also sped up

investigations into missing traders. Other measures to be introduced under the action plan included the

following:

▪ The establishment of a Joint Analytical Center staffed by several government enforcement agencies that used

merged data bases to identify risks in real time

▪ Targeting major companies involved in suspicious transactions with fraudulent organizations without

exercising due diligence

▪ Recruiting staff into the Financial Administration with increased awareness of information technology

An important outcome of the action plan has been favorable comments from judges on a general improvement

in the quality and standards of litigation proceedings by the Financial Administration.

Partly because of increased effectiveness of the Financial Administration in tackling MTIC frauds,

greater complexity is now being encountered in MTIC schemes. The Financial Administration has detected

several examples of complex supply chains and networks being used to obscure the fraud, including the use of

legitimate buffer companies to hide fraudulent supply chains and the creation of multiple companies to break

down fraudulent input tax claims into smaller amounts, which is less likely to trigger control statements or risk

profiles (so-called multi-cell fraud). The missing traders themselves are now much less likely to have assets or

hold cash, thus avoiding any recovery action by the Financial Administration. Other EU tax administrations have

also seen such increasing sophistication as they have come to grips with MTIC fraud. Further measures

updating and refining the 2012 action plan were introduced in 2016 and included both legal changes and

administrative measures.

48A recapitulative statement lists a VAT trader’s individual sales and purchases over a given threshold. Since January 1, 2014, Slovakian

VAT payers have been required to present detailed VAT ledger reports along with their periodic VAT returns, which includes detailed

information on every business transaction. Requiring such detailed transaction-based information is clearly a huge requirement and likely to

be very costly for businesses. In general, IMF advice has been for tax administrations to require information only when it is necessary and to

request information on a risk basis rather than establishing massive information reporting requirements. While the transition to VAT einvoicing

in many countries is likely to facilitate transaction-based reporting for the VAT, tax administrations should nonetheless be very

careful not to overburden taxpayers with information-reporting requirements. Many tax administrations that have established (massive)

reporting requirements have found themselves inundated with data they are not using for analysis or to improve management of taxpayers’

compliance. This means there is a high cost without a commensurate benefit, to taxpayers and to tax administrations.

IMF | How to Note 26

Improvements in VAT collections are seen by the Financial Administration as a reflection of the

successful implementation of the 2012 action plan. There was also a corresponding decrease in the VAT

compliance gap, from 41 percent of potential collections in 2012 to 26.3 percent in 2017.49 Although it has fallen,

the VAT gap has yet to return to pre-EU accession levels, and it is believed that much or most of the growth of

the gap after entry to the EU was due to MTIC VAT fraud. The possibility that there may still be significant MTIC

risks to be identified and treated cannot, therefore, be discounted. At the same time, modern tax administrations

how have at their disposal digital and analytical tools that were not available at the height of the MTIC fraud

crisis in Slovakia. Countries are starting to use technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and other

analytical tools based on “big data” to detect noncompliant taxpayer behavior that could result in VAT fraud, and

to combat the fraud itself.50

49Slovak Financial Administration, based on own VAT gap calculations. The European Commission 2019 report also confirms the trend of a

steadily decreasing VAT gap in the Slovak Republic from 2013 (estimated gap of 31 percent) to 2018 (estimated gap of 22 percent).

Differences in the gap estimates are attributable to the use of different methodologies.

50In 2019 the IMF organized a Hackathon, in close coordination with the Chilean Tax Service, to identify new technological solutions to

address specific compliance challenges. The event’s winning solution, which the Chilean Tax Service is now implementing, enab les the